Sunday, October 24, 2021. A ribbon cutting bathed in autumn sunshine celebrating a rowing club’s new home. Amplifiers and a podium. Speeches. Bubbly splashing over a squadron of new shells.

I think back on the six years it took to get to this point.

This is the story of how we got our community to entrust us with its future and a lot of its money. And how we mustered the capacity to demolish and rebuild a rowing boathouse in six months. There was no plan B.

A Farewell to Quonsets

For four decades, corrugated steel sheltered rowing shells from the elements at Toronto’s Hanlan Boat Club. In 1976, Boris Klavora, rowing coach at Upper Canada College, told his students, “Here’s the tools. We’re going to have a pro show you for a couple of hours how to put this together.” After about a week’s work by the high schoolers – with Klavora providing guidance and donuts – the steel half-cylinder Quonset hut rose.

In 1989 Hanlan added a second Quonset hut to host Havergal College. By 2000 the University of Toronto rowing team also migrated to Regatta Road. This small community grew to include recreational rowing and touring in the 2000s. Members built exterior racks and installed a donated portable trailer. The site became difficult to maintain despite heroic volunteer efforts. Exclaimed one long-time member, the Quonsets looked “like slum hovels out of Dickens.”

In the fall of 2015, I returned to coaching to help the University of Toronto alumni women’s eight prepare for the Head of the Charles regatta. It was fun, but the Quonsets were crumbling and I felt compelled to find a solution.

Two decades earlier, my father been part of a team at the Don Rowing Club which had persevered for years and had brought about a major expansion to its facility on the Credit River. I believed I could find the right people to achieve something similar.

Did Hanlan members agree about what we should do next? How would we find out? Club president Nick Matthews suggested club member Susan Wright could help. Susan advised not-for-profit organizations on how to prepare for the future. With her guidance, we organized a community consultation to identify long-term priorities.

“Our membership has doubled! Our facility is crumbling! What’s next?”

In April 2016, enthusiastic Hanlan members – masters, a growing recreational group, young competitive athletes – met to consider their club’s future objectives in a lounge above U of T’s Varsity arena. Tackling the poor state of the boathouse emerged as the key aim. Susan Wright, who led the session, polled the members and found a large majority of the attendees preferred a modest new facility over the alternative options; patching things up, or a more ambitious, multi-stage proposal. Facility development became a primary focus of the member-approved 2016-2020 strategic plan, which Susan, Shira Honig and I drafted.

I moved quickly to capitalize on the momentum generated by the session. Two weeks later, a group of seven met at the home of club member Craig Lauder. There was much to be done; identifying potential boathouse options and rack/storage solutions; determining up front financing, maintenance and storage fee models; learning about approval and permit processes we would likely encounter. Two people in particular would take leading roles in the project.

The Hunting Party

At the Hanlan strategy session, one member in the front row seemed particularly agreeable – Pierre Schuurmans. Sure enough, he later communicated to Nick Matthews that we wanted to reach out and say he was impressed with the workshop and very much appreciated the work the Board put into making it happen.

When I emailed him asking if he would join our project team, he responded within fifteen minutes: “For sure. Sounds great. Count me in.” I would have much more to say about Pierre’s contributions throughout the entire project, but he prefers I didn’t. He was a key member of the team and I was happy to work with him.

I first encountered Hanlan member Satinder Singh when I became executive director of Row Ontario, straight out of graduate school. I grew into the role with his cheerful help as vice president of marketing. An engineer, manufacturing business owner, and management consultant educated at Imperial College London. Satinder was retired but remarkably energetic beyond his 78 years. Joining the board initially as treasurer in 2016, he had the time and the technical know-how the undertaking would need.

I came to view our project as being like a duck hunt, with Pierre and Satinder as skillful, well-armed hunters. They had the patience and foresight to track an elusive target under difficult conditions, and the precision and range to hit a distant mark. I thought of myself as the pointer/terrier/retriever mix who would plunge into the reeds chasing our prey. Together, we became the boathouse committee, with Satinder as chair.

A New Concept

Satinder gave us a head start. Hanlan members had previously tried without success to identify a structure that was both suitable and affordable. Browsing the Internet for boathouse ideas in 2015, his curiosity had been piqued by a photograph of a Canadian sweep oar hanging over a bay door. Satinder eventually spoke with someone at the Lake Beresford Rowing Centre in Florida, where Canada’s national women’s team did their winter training. Their building was actually a greenhouse. Satinder’s next Google search led him to DeCloet Greenhouse Manufacturing of Simcoe, Ontario. At that first committee meeting, he presented a DeCloet design. We did not know it yet but by 2019, this concept would become reality.

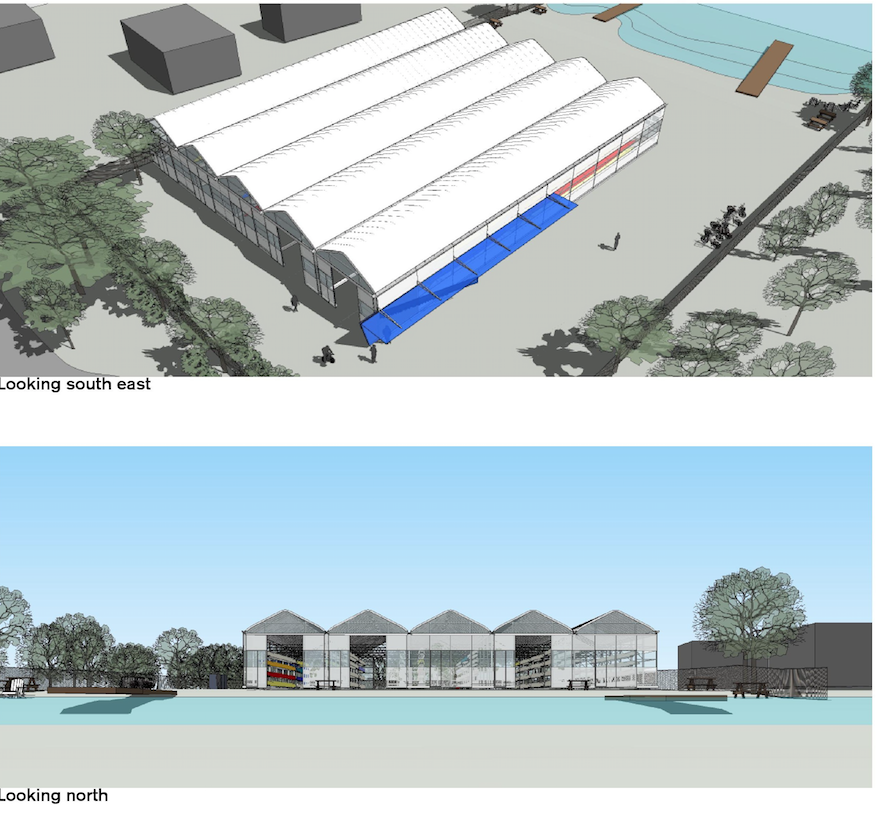

The lore of rowing relies heavily on elegance and tradition. It was difficult to find romance in the galvanized steel trusses and 8mm white polycarbonate glazing of DeCloet’ s proposal. But to me, the new design delivered something which the Quonset huts no longer could: space, light, and potential. At relatively little cost.

At 12,600 square feet, it provided much more indoor storage than the combined 7,800 square feet of the existing round-walled huts. The straight walls provided more storage options as well.

Visibility was another element. The Quonsets were gloomy, particularly before dawn. The translucent cladding and roofing, combined with the LED lighting designed by club member and lighting specialist Harold Murray, would give the boathouse a luminous quality making it highly visible even from the lake.

It also mattered that we saw the $200,000 building-and-installation quote fitting within the initial overall $500,000 project budget estimate. The concept was a pragmatic and achievable solution to the urgent problem of replacing the Quonset huts. It would allow future members to turn their energies towards improving the quality of the rowing experience.

Before proceeding with the DeCloet design, we sought comparable proposals and quotes from others. In May 2016, Craig Lauder, Alanna Komisar and I drove to the Niagara Falls Rowing Club, which had just built its own two-bay boathouse using a different greenhouse supplier. Pierre, Satinder and I also went to Newmarket to see one of DeCloet’s installed structures in person. Wandering among potted plants and breathing humid air, it helped to learn that such buildings could shelter boats and oars, not just begonias and orchids. By the end of 2016, we were confident that DeCloet was the right fit for us.

Enter the Architects

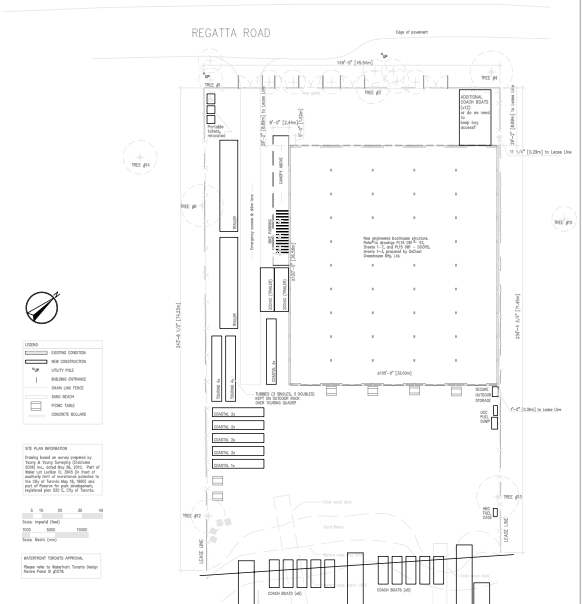

Club member and architect Tristan Armesto reviewed our plan and helpfully pointed out ways to ensure people, boats and trailers could circulate effectively. Our six bays became five, we trimmed the dimensions to a still-generous 120 x 105 feet overall, and shifted the footprint to the eastern edge of our site. Tristan gave us a miniature foam model and digital images, which we used to introduce the plan to our members and other stakeholders.

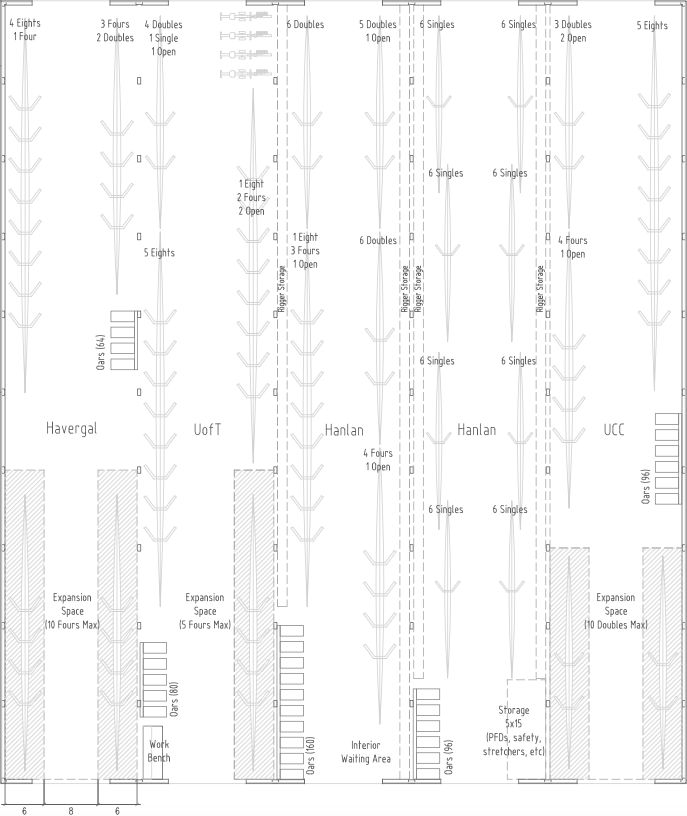

Joanna Kolakowska and I were colleagues at the Toronto 2015 Pan American Games rowing venue on Henley Island. I was a sport manager. She was a designer and manager of the temporary overlay plan. Joanna skilfully created multiple computer-assisted drawings to ensure our boathouse would have ample room to store boats, oars and other equipment. These diagrams helped persuade stakeholders. They also helped us determine the size and placement of the storage racks.

Kelly Brigley was another rower-architect who guided us. She often pointed out things that we had not considered. Our budget was modest, but Pierre, Satinder and I concluded it would be wise for the club to pay professionals to help handle the extensive regulatory processes associated with construction in Toronto. In the spring of 2017, Hanlan Boat Club hired Robert Macpherson and Lucie Richards of Lieux Architects to assist.

Tristan Armesto’s scale models on top of a satellite image.

Permit Purgatory

On our boathouse tour, the President of the Niagara Falls Rowing Club cautioned that construction approvals could lead to major setbacks. Gulp. We were building on leased, prime waterfront parkland in Canada’s biggest city. This involved a multi-phase process with Waterfront Toronto.

Waterfront Toronto already knew about Hanlan, having previously granted phase-one approval to an earlier plan that Tristan Armesto designed. In June 2016, Nick Matthews, board member Alison Collins-Mrakas and I met with staff to explain our change to the greenhouse concept. Chris Glaisek, chief planning and design officer at Waterfront Toronto, liked the elegant simplicity of the design, but needed much more technical detail.

Waterfront Toronto’s design review process took most of 2017 to complete. In March, I officially introduced the new plan. In June, with Robert Macpherson and Lucie Richards, we presented the concept in detail. By phase three in October, a major new component would be required; a detailed landscaping plan. With Robert and Lucie focusing on the building itself, who could handle this?

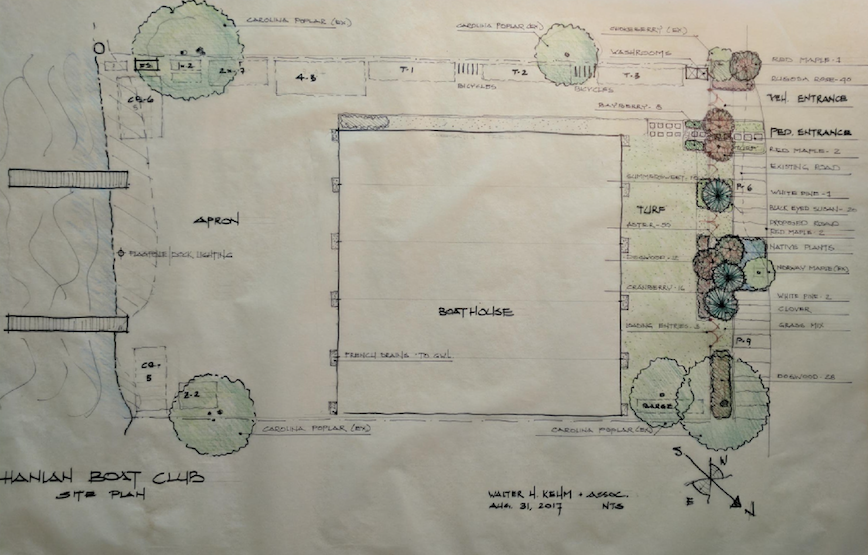

I first met Hanlan member Walter Kehm during my time at Row Ontario when he was founder of the new Guelph Rowing Club. Walter was a prominent landscape architect well-known to Waterfront Toronto. He designed Tommy Thompson Park and Trillium Park, which were significant enhancements to the city’s waterfront. I called, asking if he would recommend someone. Walter then personally designed and presented our landscaping plan. We were delighted.

At the decisive final meeting, Robert, Lucie and Satinder delivered even more detailed information on the site and structure. Walter then addressed what really mattered to the panel – the transformation and beautification of the city.

“This small redevelopment could be a springboard for a master plan on Regatta Road,” he enthused. “This is a precedent-setting project. From small acorns, mighty oaks grow.” This, coming from an eminent authority in landscape architecture, was music to the ears of the design review panel. We got our approval.

Note the diving board-like docks have not been built as shown!

Making Deals

Despite great progress, by the autumn 2017 it was apparent that our goal of having a new boathouse in place for the 2018 season was overambitious. It took us another year to do the job. But we had new confidence and a firmer understanding of how much money we would need for the biggest line item.

In fact, for some years Hanlan had already been saving money for a boathouse. But these funds were merged with other club revenues and the total amount was unclear. Joining the board as Treasurer, Satinder rearranged the banking and accounting systems to enable tracking of the restricted funds and determined there was already about $232,000 in the bank. The project, which would ultimately cost $688,000, began to look more achievable. The balance of the funds came from three other initiatives: storage agreements, member donations, and corporate support.

The most complex of these sources were the agreements, which redefined Hanlan’s relationship with the schools. The four entities loosely co-existed on site for decades, and the schools each had a representative on the Hanlan board. We proposed a significant change: replacing the schools’ direct involvement in the club’s governance with clear, detailed tenancy agreements. It would take deft negotiation and almost two years to get these deals done.

Our initial meetings with the athletic directors were friendly but non-committal. Based on ongoing feedback, we developed a draft memorandum of understanding, with the help of long-time member and corporate lawyer Harry Vanderlugt. He told me with a grin that legal departments at large institutions often handed these comparatively small assignments to junior lawyers eager to prove their zeal. With Harry in Hanlan’s corner, MOU drafts flew back and forth throughout 2018 and into 2019.

Each school agreed to pre-pay five years of their determined annual rental amount, with the money going directly to boathouse construction costs. The MOUs brought in $90,000 for the boathouse by the spring of 2019.

We developed a similar process in miniature for the scullers storing their private shells in the new boathouse. Harry and I adapted the singles’ storage policy of the Ottawa Rowing Club. The five-year pre-payment scheme generated a further $34,000.

A key success of this venture was that the allocation of racks went smoothly thanks to members MaryAnn Crichton, Barb Prevedello and Eric Szonyi. The trio created an ingenious process that blended each sculler’s preferences with the impartiality of a lottery. In the end, everyone was satisfied.

Twisting Rubber Arms

Throughout the campaign, one of my tasks was communicating the boathouse committee’s progress to the Hanlan membership. I did this informally, and through various club meetings and media platforms published by board members Melanie McNeill and Kirsten Ryan. Steadily building members’ interest and confidence in our undertaking paid off.

We then asked for donations from Hanlan members and alumni. Satinder and I discovered the National Sport Trust Fund would facilitate this. The NSTF enables amateur sport organizations to establish revenue generation programs for which charitable tax receipts can be issued. Once approved, Hanlan approached prospective donors with this key incentive.

Pierre, Satinder and I met with Nick Matthews to identify members and friends of the club who might make larger donations, and each of us took on a share of the asks. With these initial pledges building momentum, we made further appeals. Hanlan supporters were phenomenally generous, bringing in $135,000. Initiatives implemented by board member Shawna Pereira generated a further $11,000.

Just in time for the official ribbon cutting in 2021, Hanlan Boat Club created a brick landscaping feature at the boathouse entrance to recognize individual donors.

More Permit Purgatory

Before we could put shovels into the ground, we needed a building permit.

We applied to remove seven trees on our site. Fortunately, these were mostly Carolina Poplars, an invasive species. Nonetheless, we were charged for their removal and committed to planting seven new trees as Walter Kehm had directed. Anticipating eventual building permit approval, I also obtained Parks department clearance to do the construction activities on our parkland site and adjacent roadway.

Satinder worked closely with our architects, DeCloet, and electrical engineering consultants on the countless details of our building permit application. The key aspects he dealt with included the electrical design and the addition of person-doors to each of our ten bay doors in order to meet building codes. This took months, but we submitted the whole lot to the City’s Building department.

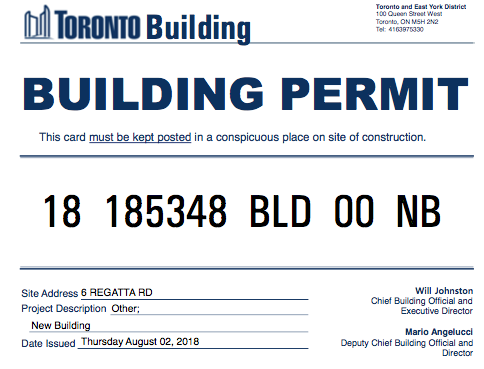

After a final flurry of approvals, payments, and submission of certificates of insurance, our building permit was issued on August 2, 2018. It was something to celebrate.

Exodus

Vacating our site in October 2018 was an “all-hands” portion of the project.

Each of the schools loaded their equipment onto trucks and trailers, bringing them to winter storage locations. Many of the single scullers did the same with their boats. This was similar to the de-rigging and loading operations typical for a regatta. But Hanlan’s task was bigger overall. Everything had to go. But where?

The club organized work parties led by head coach Iain Wilson and members Kirsten Ryan, Shawna Pereira, Hugh Fletcher and Eric Hall. We purged ruthlessly. Broken seats and Macon oars, abandoned hats and water bottles, torn PFDs, splintered plywood. Into the dumpster it all went. The club truck made several trips to drop off empty fuel canisters and other hazardous waste. Our Junior rowers hauled a dozen motorboat hulls to our neighbours, Water Rats Sailing Club. Water Rats also courteously allowed us to store our dock segments on their site. We floated these over and our rented crane stacked them on their shoreline.

Everything else went into five rented 40-foot storage containers grounded on Regatta Road. This took more permits and insurance certificates, and the buy-in of the other boating clubs on Regatta Road. Hugh Fletcher and his crew took on the logistical puzzle of fitting shells of varying types, oars, outboard motors, bags of PFD’s and everything else into the containers. With our site vacated, it was time to bring the heavy machinery.

Moving Hanlan and Earth

The Toronto port lands were created by dumping construction rubble over a marshland. A geotechnical report for our site declared the ground to be “unsuitable for supporting foundations”. When we started digging, the cold November rain turned the clay and brick debris into a slick, gray quagmire. It clung heavily to steel-toed boots, and the construction vehicles often got stuck. We constantly unearthed challenges that required rapid problem-solving.

Our search for demolition and excavation contractors turned up some eye-watering quotations. But Satinder found a sole operator from Orangeville who could do the work for a reasonable price. Costs rose as the scope of our needs grew, and work was hampered by weather conditions. It was tough to manage, and hiring a professional to direct the project was beyond our means. Satinder, with my assistance, was on site to handle the day-to-day oversight through this tricky phase. We were all aware that time was ticking to get things done for spring.

Demolition went shockingly quickly. Within a week of rowers leaving the site, the Quonset huts, the portable trailer and trees were all pulverized and removed. The landscape of mangled corrugated steel and splintered wood didn’t make me sentimental. My eye was on the next steps.

“To deal with elevation and flooding”, Walter Kehm declared, “we need a proper grading and drainage plan.” In recent summers, Lake Ontario reached record levels, leaving much less shore-side operating space. Walter created a scheme to put us on higher ground, and the contractor carved a pit four feet below the planned floor grade. That soil was distributed over the rest of the site. Because of the clay, we needed a solid to a base for heavy machinery, and a retaining wall to hold the aggregate together. Satinder found a supplier for both. Our contractor placed about one-hundred 900lb concrete blocks along the edge.

We needed high-quality fill material for the excavated space and the surface of the site. Where would it come from? Two years earlier Satinder had gotten us a meeting with Lafarge Canada, a supplier of building materials. We built a relationship with the company and they generously gave us about $30,000 of aggregate at no charge. With Satinder coordinating the operation, 120 dump truck loads of aggregate made their way to Hanlan from their plant in the Portlands. Club members now have more room to circulate on site and are high and dry in the best sense.

Another major complication came. Our architects worried that the concrete footings would not hold up on our site’s unstable soil. Satinder engaged a structural engineer to check. She determined that the only secure foundation would be steel helical piles drilled down to bedrock. This was a significant and unwelcome cost increase. But none of us wanted to be responsible for building a shaky structure. The board approved this additional expenditure. Through December, contractors drilled 66 piles up to 40 feet down at precise intervals. Hanlan volunteers cut and placed PVC sleeves over each to insulate them from the surrounding aggregate. We were ready for the building to go up.

Test of Metal

Record-breaking snowfalls. Sustained frigid temperatures. High winds. It couldn’t have been fun for the DeCloet crew installing the boathouse’s metal frame through the winter of 2018/19. There were small snags such as fitting the posts to the helical piles, and uncooperative sliding door components. But DeCloet kept us on schedule. The boathouse was in place by mid-March.

At about the same time a further 4.5 metric tons of metal were being turned into boat and oar racks. As early as 2016, we recognized the need to find the right storage solution. We looked for existing generic and rowing-specific options, but nothing suited us.

Once more, Satinder Singh stepped in. Through 2018 he worked with a metal engineering firm to design and produce our racks. By the fall, he presented prototypes and made more adjustments. In their final form the boat racks had a sliding mechanism, and could be set at adjustable levels for a variety of hull sizes. The oar racks were “side-loading” for ease of access. This increased storage capacity and flexibility was a tremendous step up from the Quonset era, at a price we could afford.

Leaving the Hunt

After three years the building was nearly complete. But just as we were closing in, I had to leave. The employment offers were too good to refuse – a challenging assignment in Bosnia, and a unique opportunity in Panama. These months-long journeys limited my ability to see the boathouse build entirely through. I resigned my board position and left Hanlan in May 2019. It was the right call for me, but was not without cost to the project.

We had fundamentally succeeded. But there were many details still to iron out, and this intense final phase came with time, space and money pressure. It took some weeks to complete the electrical, engineering and landscaping work in order for the City of Toronto to issue an occupancy permit, and then for the racks to be installed. Through this period, rowers operated “regatta style”, with boats stored outside.

Satinder had done the lion’s share of the sitework to get us to this point, juggling the construction and the attendant bills to be paid. But now others wanted a say and felt they could do better, despite his accomplishments in a difficult role. It got so acrimonious that Satinder resigned. The boathouse committee disbanded and Satinder handed over responsibility to the club president.

At the ribbon cutting ceremony over two years later, among all the accolades given, there were none for Satinder Singh, whose sustained voluntary effort was crucial to the project’s success from the outset. No one had done more to get the boathouse built, and Hanlan should have recognized him. It was an embarrassingly graceless omission by the club’s leadership.

I was proud of my role, but with a streak of ambivalence due to the ill feeling. It was not what I had imagined, but we pulled off something unique. The last time a boathouse was built in Toronto was the Argonaut Rowing Club’s facility in 1947. For a small organization like Hanlan, our new addition to the waterfront was a major technical and financial achievement, one which a professional construction estimator rated was good value for the money. My vision was to bring together a range of talents and experience to make it happen. Mission accomplished.

On Being Builders

The work of rowing is endless. Since the building went up at Hanlan, there have been further site improvements, and a pandemic to navigate. There are new people and new boats. For the first time in the club’s history, rowers can train indoors on site year-round. A new strategic plan is in the works. The boathouse is an asset which allows Hanlan members to consider exciting future possibilities for rowing in Toronto.

Boathouses come and go. Over the past hundred and fifty years, Toronto rowers have created a dozen homes for themselves along the waterfront. Whether it is years or decades later, storms, fires, wrecking balls or redevelopment claim them all in the end. But for as long as they last, boathouses give people a place to create friendships and community through an amazing sport. They are a lakeside springboard from which we escape our cares.

People also come and go. Everyone who contributed to Hanlan’s undertaking made our small part of the world better for those around us and for people we will never know. To build a boathouse, we confronted hard numbers. We got dirty and shivered on a construction site. We did not know how it would turn out. It was fun at times, uncomfortable at others. It took years of dedication. Together we achieved something uncommon. May you have the same good fortune.